For decades Youssouf Ahamada Bachirou was one of the most influential and trusted people in football in Comoros. Despite the fact that it was an open secret he sexually abused teenage boys.

By Romain Molina

“Ten years ago, I wrote an email to several local media. I didn’t put my name in it but I told my story, I told them what happened…”

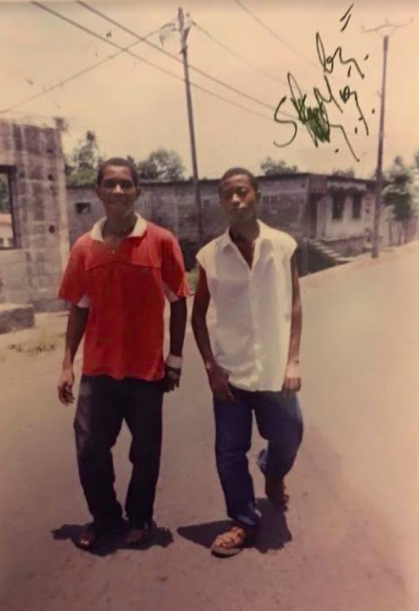

Khaled Simba, a former player of Flèche Rapide, a small youth team linked to Elan Club, one of the biggest clubs in Comoros, is taking a break. For more than an hour he’s been speaking about his own experience after all these years of silence.

“I tried to advance in my life to become the man I am today. What happened twenty-two years ago almost cost me my life. It was so close to destroying me forever. It’s still hard to tell today. That’s why, ten years ago, I wrote this email. Only one person answered me, can you imagine? We talked, he tried to help but nothing happened. At the time, I felt guilty because I thought: ’If I talked before, maybe it could have saved some kids.’ That’s why I’m talking publicly now. “

Growing-up in Mitsoudjé, a small town located 15 kilometres away from the capital Moroni, Khaled Simba spent his time between school and sports. “I played basketball and football,” he remembers.

“I was a...