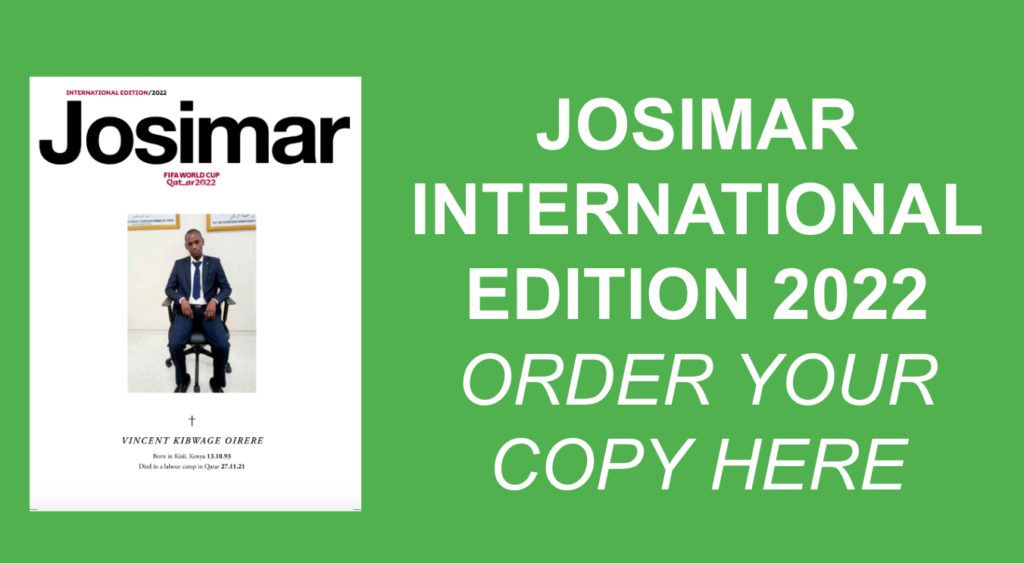

Politicians, leading academics and international trade unions have praised Qatar for its reforms since they were given the hosting rights to the 2022 World Cup in 2010, following a corrupt process. But how are things really on the ground?

Are the reforms for real? In March, five journalists from Josimar travelled to Qatar.

Nearly everyone you’ll read about in this issue has taken a huge personal risk by talking to us. With one exception, all interviewees have been anonymised for their own safety. Qatar is a police state without freedom of expression, freedom of the press or freedom to organise. It’s a dystopian society where many migrant workers, and some citizens too, live in fear. One of the interviews was done by telephone shortly before we went to print.

You can also donate to our work HERE.

Working as a journalist inside Qatar is difficult. We travelled there on tourist visas. After getting through immigration and customs at Doha’s international airport, we quickly deleted Etheraz, the smartphone app mandatory for every visitor. The app was introduced as a Covid-19 tracing tool, but it also has a number of properties that can be used for surveillance and manipulation. We brought extra phones that were not smartphones and we never used wifi.