According to Fifa, Qatar 2022 is to be the 'greenest of all World Cups'. But independent reports show that far from being the first carbon-neutral global sports competition in sports history, as promised by Fifa president Gianni Infantino, the forthcoming World Cup will be the dirtiest ever staged.

By Philippe Auclair

The World Cup in Qatar will at least double the carbon footprint of the 2014 and 2018 tournaments – with hardly any significant mitigation to offset its environmental impact.

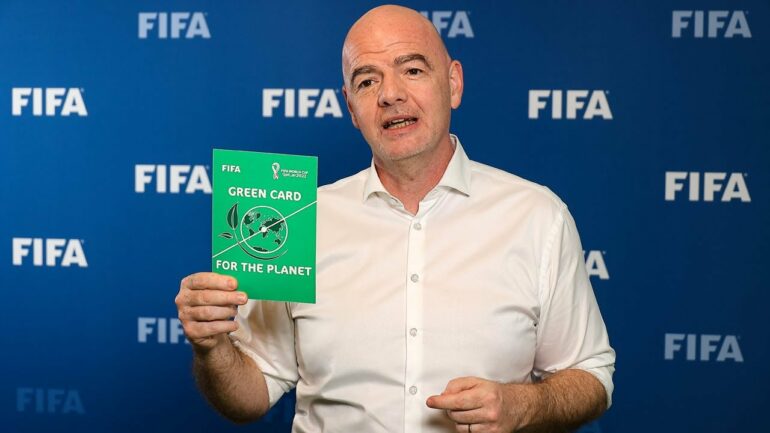

5 June 2022, World Environment Day. In a short film posted on Fifa's official YouTube channel, Gianni Infantino brandishes an oversized 'green card' stamped with the logos of Fifa and Qatar 2022 and reads from the autocue: “I’m asking everyone who loves football and who cares about the environment to raise FIifa’s Green Card for the Planet.”

Not many did. At the time of writing, five months later, Infantino's appeal had been watched by a grand total of 591 people.

But does it matter? After all, the one thing that really matters is the message in itself, awkward as its presentation might have been; and the message was, in Infantino's own words: “Fifa is playing its part, with our aim to make the Fifa World Cup Qatar 2022 carbon neutral.”

Sceptics immediately homed in on the strategically-placed 'aim', which could exonerate Infantino if the World Cup didn't turn as green in the wash as hoped in the end. Yet, at least, Fifa was showing intent, as it had done when it had launched its 'Climate Strategy' at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November 2021. World football's governing b...