How a whistleblower exposed the dark truth of Qatar’s World Cup.

By Nicholas McGeehan

The last messages from Abdullah Ibhais arrived at 04:45. “Police came to take me. They are taking me to prison now.” He managed to call one of his interlocutors, the German journalist Benjamin Best, but by the time others awoke, Abdullah had gone. He had managed to stay at liberty for nearly four weeks after he went public with his allegations against his former employers’, Qatar’s 2022 World Cup organisers, the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy. His claims, published in Josimar, were explosive – that the Supreme Committee had covered up their involvement in migrant worker abuses, and then instigated a malicious prosecution against him after he took an internal stand on the issue – and he had a trove of documentation to back up his allegations, only some of which have been published. That’s probably why they came for him, to shut him up, although Abdullah’s arrest could have come at any time, given that he had a 5-year prison sentence hanging over him for what he says were trumped-up bribery charges. In December 2021, exactly one month after he was taken from his home and his wife and two young sons, Qatar’s court of appeal upheld his conviction. The sentence was reduced, without explanation, to three years.

It is, of course, fascinating to speculate on why he did what he did, and to delve into the bizarre details of the Supreme Committee’s internal investigation, and the absurd court judgments, and the contradictory witness statements, but all that this will tell you is that Abdullah was stitched up. The bigger and more important story is what Abdullah was telling us about Qatar’s World Cup, because what he revealed is how Qatar and FIFA stitched us all up.

Not Our Workers

Qatar had some very significant problems to deal with after it won its World Cup bid in 2010. Geographically, Qatar is about half the size of Wales but its population is overwhelmingly concentrated in Doha – it is more or less a city state and the hosting of a World Cup in one urban centre meant it needed to completely overhaul and upgrade its transport infrastructure. And it needed to do this using an army of migrant workers from some of the poorest parts of already very poor countries in south Asia, with a labour system that was likely to put quite a lot of them into conditions either close to or legally classifiable as slavery. For the organisational and logistical challenges associated with the construction, Qatar could simply throw money at the problem, but the migrant worker issue was more complex. Qatar could either approach the issue as a labour rights problem and radically reform its labour system, or it could approach the issue as a PR problem and throw money at it. The key thrust of Abdullah’s allegations is that Qatar went for the PR solution, and Abdullah provided a lot of evidence to back up his claims.

(Abdullah Ibhais (in green) advises a senior Supreme Committee member against making statements distancing the organisation from a migrant workers’ strike in August 2019.)

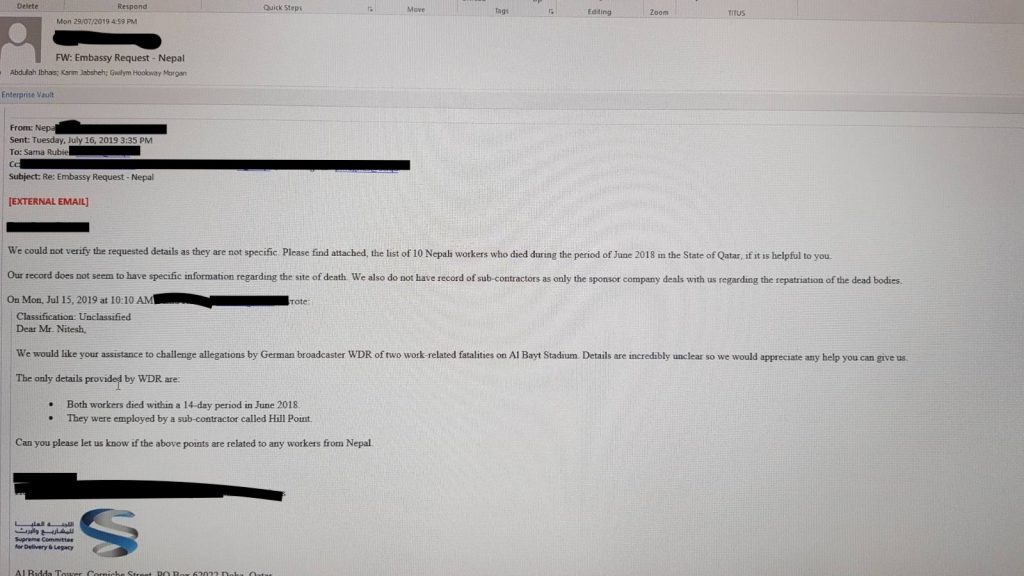

In the WhatsApp chats that Abdullah claims are at the root of his problems, the Supreme Committee’s ‘crisis comms’ group was discussing a strike in August 2019 that had left a very large group of migrant workers unpaid for several months, the conversation begins with the Secretary General of the Supreme Committee, Hassan Al-Thawadi, asking the group “can we go out and have our social media guys clarify that they aren’t related to 2022.” The SC wasn’t disputing the fact of the strike, or that it had left migrant workers in one of the richest countries in the world dependent on charitable donations of food and water to survive, they just wanted to put out a public statement that the workers on strike hadn’t been building stadiums. This wasn’t the first time this happened. Copies of an email exchange between the Supreme Committee and the Embassy of Nepal from July 2019 show a Supreme Committee employee writing that “we would like your assistance to challenge allegations by German broadcaster WDR of two work-related fatalities on Al Bayt stadium.”

This wasn’t an attempt to challenge the assertion that the men had died, it was to challenge the assertion that the men had been working on stadium construction when they died. “Our records does not seem to have specific information regarding the site of the death” replied the Embassy.

These exchanges are illuminating in that they neatly summarise how Qatar has addressed the migrant worker problem – provide enhanced protection to the one percent of migrant workers building stadiums as a means of deflecting attention from the conditions endured by the 99 percent building and servicing everything else. From a public relations perspective, it was a smart decision, because it was obvious that many journalists and their commissioning editors would be looking for abuses involving stadium workers, but from a workers’ rights perspective it was a disaster.

Qatar needed a lot more than eight new stadiums. It needed new roads, new hotels, new trains, new tracks, and a new deep-sea port to import the raw materials. It needed a new city, Lusail, and it needed new sewerage, drainage, water, and seven electrical substations to power it. And to make this possible they needed many hundreds of thousands of migrant workers, and they all needed accommodation. In 2012, the International Labour Organisation estimated that Qatar would need an additional one million workers to make the 2022 World Cup possible. Qatar’s rate of net migration between 2010 and 2015 was the highest in the world (54.7 per 1000 inhabitants). Yes, some of this would have happened anyway, but the 2022 World Cup was the catalyst and the driver of the reconstruction and expansion of Doha.

If the first conceit was that only stadium workers were linked to Qatar’s World Cup, the second conceit was that the Supreme Committee could effectively protect the tiny fraction of workers for whom it had assumed responsibility. As a WhatsApp discussion between Abdullah and one of his former colleagues reveals, the Supreme Committee was well aware that it couldn’t.

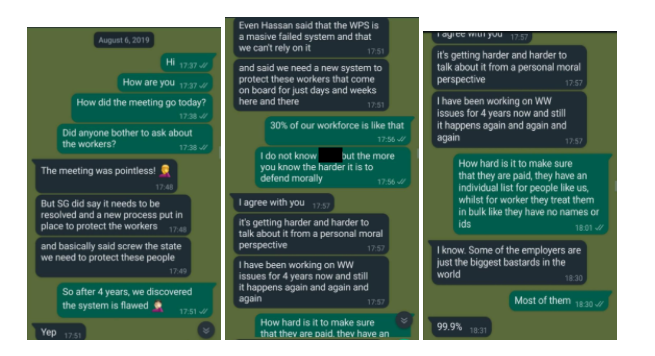

The conversation below took place on 6 August 2019, two days after the initial WhatsApp group conversation about a strike over unpaid wages involving a large group of migrant workers in the Al-Shahaniya labour camp outside Doha. Abdullah had provided evidence to his colleagues and his superiors that some of the workers were actually involved in 2022 stadium construction and were in dismal conditions as a result.

Abdullah’s colleague bemoans the Supreme Committee’s inability to provide basic wage protections for “workers that come on board for just days and weeks.” Abdullah replies that “30 percent of our workforce is like that.” Qatar’s construction sector runs on long and complex labour supply chains that partly explains why so many migrant workers end up not getting paid, and as Abdullah’s colleague makes clear, non-payment of wages was a big problem even on World Cup projects. “I’ve been working on WW [worker welfare] issues for 4 years now and still it happens again and again and again,” he says. He also explains the other main reason why it keeps happening – “some of the employers are just the biggest bastards in the world” – and he makes clear that by “some” he means “99.9 percent” of them. The context to this is that many of the construction companies in Qatar are owned by powerful members of the ruling family, as in the case of the August 2019 strike, or other powerful elites. The line between the state and the private sector in Qatar is blurry, sometimes to the point of non-existence, and construction projects are a very effective means of getting the revenues from its vast fields of liquefied natural gas into the pockets and offshore bank accounts of its elites, many of whom also hold key government positions.

The SG to whom Abdullah’s colleague refers in the conversation is the Supreme Committee’s Secretary General, the charismatic Hassan Al-Thawadi. When Al-Thawadi looks you in the eye and tells you that workers’ rights is in the Supreme Committee’s DNA, you certainly want to believe him, so it’s not entirely surprising to see him reported as saying “screw the state we need to protect these people.” At the same time, the notion that the Supreme Committee isn’t part of the Qatari state is fanciful. On the contrary, it is a key government institution with the Emir as its chair. It just isn’t part of the Qatari state that had any real capacity to protect workers’ rights because it was never set up to do that.

The Qatari Ministry of Rapport Building

The government ministry responsible for protecting Qatar’s migrant workers, including all of those involved directly or indirectly in World Cup construction, is its Labour Ministry. Few, if any, journalists will have been entertained in its sedate, kitsch interior, instead they are whisked into the altogether flashier meeting rooms in the futuristic Al-Bidda Tower, overlooking Doha’s palm-fringed corniche, where a cosmopolitan staff can flip between Arabic or faultless English, talking earnestly about the challenges of protecting migrant workers, but then excitedly about the progress that is being made. Those who drink the kool-aid in the Al-Bidda Tower leave it thinking that Qatar should host every World Cup. Those who then go on to drink the Arabic coffee in the Labour Ministry leave it thinking that the challenges are probably a lot more significant than the progress.

Abdullah belonged very much to the Al-Bidda Tower set, a smart, ambitious 35-year old Jordanian who moved to Qatar to work in public relations in 2012, and rose quickly through the ranks of the Supreme Committee after joining them in 2014. By 2018 he was the Arabic language media and social media manager, in charge of a large team and with significant responsibilities. He knew quite a bit about workers’ rights too. During an early discussion, before he went public with his story, he spoke at length about the Supreme Committee’s heat-protection system, displaying impressive technical knowledge of heat protection systems. He said he had complained about the Supreme Committee’s use of a monitoring system that was facilitating night-time shifts in the hottest months of the year, when high levels of night-time humidity should have precluded the performance of any work. His story was wholly consistent with research on this topic, which suggested that the Supreme Committee had knowingly subjected its workers to extremes of heat and humidity that would have put them at risk of heat-related illness. But he wasn’t a workers’ rights specialist and neither for the most part were his colleagues. The Linkedin profile of Abdullah’s colleague who called Qatari employers “bastards” describes him as “an experienced international communications specialist with nearly 15 years’ experience in both corporate and consumer PR and Communications.” The Linkedin profile of the Supreme Committee employee who contacted the Nepalese embassy seeking assistance in challenging German media reporting of migrant worker abuses on stadiums describes her as “an experienced senior public relations specialist with a demonstrated history of working in the sports industry.” The Supreme Committee oversaw the construction of stadiums, but when you look at how the organisation is staffed, and how it operates, it looks and feels a lot more like a public relations firm with some construction interests, and as a voice message that its Secretary General sent to key communications staff (the date is unclear but appears to date from 2019), they took a smart and sophisticated approach to media relations.

“We do have to have a strategy in terms of providing off the record feedback. Being able to engage with these people off the record and discussing and building relationships with these people when it comes to these briefings. We have to have that engaging capability, not necessarily giving an official statement and that’s the difference, I’m not saying giving an official statement, I’m saying building the relationship and the rapport so we can start providing briefings to these people.”

The value of this tactic of informal briefings has perhaps never been more evident than in the aftermath of Abdullah going public with his story, when his former Supreme Committee colleagues briefed journalists in private, attacking Abdullah’s credibility, questioning his motivations, and claiming to have evidence of his guilt. The message was delivered in familiar sounding accents by men with familiar sounding names, who have spent years building relationships with the international media. Nobody actually ever saw the evidence of course, but once you’ve built the relationship and the rapport, it’s a lot easier to sell whatever line needs to be sold to kill a story, or at least inserted into the story. There is no little irony in the fact that the very skills that Abdullah practised and honed have been used against him, and most effectively.

It’s worth repeating that it was the Supreme Committee that instigated the criminal investigation into Abdullah, claiming that he had links to a senior figure within Saudi Arabian media circles (at a time when Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were blockading Qatar and seeking to strangle its supply chains) and was attempting to corrupt a bid for a social media contract, despite no evidence of either. Given that they are essentially part of the Qatari state, the Supreme Committee’s refusal to condemn Abdullah’s demonstrably unfair trial is not necessarily surprising, but what about FIFA, which has a human rights policy and a platform for whistleblowers to submit complaints? Abdullah submitted a whistleblower complaint, but his time working for the Supreme Committee meant he knew that FIFA was highly unlikely to take his side. And he was right.

Revolving Doors

“Hi I’m John Barnes. And I’m Jason McAteer. And this is Qatar. Only six hours from London. Dead simple. We didn’t need a visa, just straight on the plane.” So begins ‘From Liverpool to Doha’, a 5-minute video released in December 2019, the month before Liverpool FC travelled to Qatar for the World Club Cup. In a document drafted by the Supreme Committee the month previously, they note that “the activity has to be managed carefully to avoid the potential backlash that can come from ‘paid voices’ defending Qatar” and added that it “had to come across as authentic.” Viewers can make their own minds up on that one.

The Supreme Committee were apparently concerned about the formal and informal travel advice that was available to Liverpool fans and the document outlined their strategy to address this: “Whilst this is all important information for fans and stakeholders to receive, it is based on local laws rather than the reality on the ground. The SC and all tournament stakeholders, therefore, need to be able to tell the stories from the host country’s perspective and dispel any myths there may be, reassure fans that the fan experience will be fantastic and that issues such as LGBT+, workers’ welfare and cultural norms have been well considered and the country is ready (and excited) to host fans from around the world.”

However, according to the document’s meta-data, it wasn’t drafted by a Supreme Committee employee, but by a FIFA employee using a Supreme Committee email address. FIFA’s explanation for this – they responded with atypical speed to Josimar’s questions – was that the individual in question, who had worked for the Supreme Committee for nearly two years from 2015, had simply designed the document template and that he was not involved in communications strategy either for FIFA or previously for the Supreme Committee, even though his Linkedin profile suggests experience and competency in this area. It is of course possible that the Supreme Committee was still using the same document template three years after its designer left their employ, and has not actually embedded itself within the Supreme Committee’s spin machine, but Abdullah provided further evidence of the extent to which FIFA and the Supreme Committee work in tandem on messaging around the World Cup.

A WhatsApp conversation with his boss from 2019 shows them discussing the need to have FIFA approve a Supreme Committee public response to allegations of migrant worker abuse documented by German journalist Benjamin Best and aired by German broadcaster ARD. Abdullah said that it was standard practice for FIFA to approve all statements put out by the Supreme Committee in relation to workers’ rights issues. FIFA’s media office made no attempt to deny this allegation when it was put to them by Benjamin Best, saying that “FIFA and the SC are in regular contact and check information that refers to topics that are under the responsibility of their counterparts.” FIFA’s response to the Abdullah Ibhais case makes complete sense if they see their role as to assist Qatar in promoting itself to the world through the power of football, and it is clear that FIFA is aware of the services it can provide in this regard.

Ahead of the 2018 World Cup final in Moscow, Gianni Infantino said that the world “all fell in love with Russia” and that “the World Cup has changed the perception of the world towards Russia.” Putin thanked Infantino for “your glowing assessment of our efforts” when presenting him with an Order of Friendship medal at the Kremlin in May 2019. Infantino is unlikely to be looking for photo ops with Putin any time soon, but expect to see plenty of shots of Infantino in Qatar for the next six months, because thanks to the work of the Swiss Newspaper SonntagsBlick, FIFA finally admitted in January 2022 that Infantino had actually been living in Qatar since October 2021. “Apparently he doesn’t feel comfortable in Switzerland,” tweeted his predecessor Sepp Blatter, pointedly. He feels quite comfortable in Qatar, it seems, where he has been happy to trot out the Supreme Committee’s PR lines, recently telling the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe that only three people have died building football stadiums for the 2022 Qatar World Cup. It was a grossly misleading claim (and one that the Supreme Committee had already planted in the media a few months previously) ignoring 92% of the deaths on stadium construction – 58% of which remain unexplained -, focusing on projects that account for only 1% of construction in Qatar, and glossing over the broader pattern of migrant worker deaths in the country, which has resulted in thousands of unexplained deaths and which has been documented in meticulous detail. Just as in the Ibhais case, even though the evidence tells a completely different story, Qatar and Infantino have built the sort of rapport that facts and evidence can’t shake.

Abdullah made his feelings clear to FIFA a few weeks before that early knock at the door from the Qatari police. Frustrated after weeks of his calls and messages to FIFA went unanswered, he sent a message via Signal to the staffer who had initially encouraged him to submit a complaint. “Hello. I know my message will find no answer. I am sending it however to prove to myself how aligned FIFA is with the SC, regardless of any facts on the ground. FIFA did not move to protect the lives of workers on the ground, so what hope do I have to see it move to protect my rights and my family.”

It’s vital that we recognise the precise significance of what Abdullah Ibhais has told us about Qatar’s 2022 World Cup, as well as the cost to him and his young family for doing so. This account of his case and analysis of the documents he shared is not intended to present the Supreme Committee as evil geniuses who hatched a devious plot to blind us to the realities of what was happening in Qatar. Anyone who goes to Qatar just has to speak to a hotel worker or a taxi driver to know the truth, which is too glaringly obvious to be hidden, and anyone who has followed or interacted with the Supreme Committee knows what it is. But with sport, and particularly football, in the dock right now, we need to reappraise its cosy relationship with authoritarian regimes who use and abuse it for political ends, and recognise how easy it is for the public relations tactics they employ to warp people’s perceptions and lead them to scuttle their principles. Abdullah lifted the lid on how it happened in Qatar and it is yet another appalling indictment of the state of the game that in the year of Qatar’s World Cup, that the whistleblower who ran its Arabic public relations is languishing in a Doha jail, while FIFA President Gianni Infantino is in a plush Doha residence, with a Russian medal of honour pinned to his chest.