For months, the Russian army has secretly recruited hundreds, if not thousands, of jobless migrant workers in Qatar to fight on the frontline against Ukraine.

By Sam Kunti and Håvard Melnæs

On 15 May, Marfo Nicholas Kwaku from Ghana was pictured holding a rifle and wearing a helmet, a tactical vest and camouflage fatigues. There are no insignia on his outfit. He looks into the lens with a serious stare. Behind him, at the entrance of a bunker, stands another soldier.

How did Marfo, a former school teacher hailing from rural West Africa, who went to Qatar in 2019 to work at a fish factory where he stayed for the better part of six years, with no experience as a soldier, end up in Vladimir Putin’s army, embroiled in the Russian invasion of Ukraine?

The war has already claimed the lives of nearly 50,000 Ukrainians, with another reported 380,000 wounded. According to reports, one million Russian soldiers have been killed or injured, including over 250,000 confirmed deaths. The enormous number of casualties has made Russian president Vladimir Putin search for new avenues outside his regular army to recruit soldiers. First, convicts were released on a large scale from Russian prisons to cover up for the huge losses. Two years ago, in October 2023, the prison population had fallen from 420 000 to 266 000, a decline that was attributed to the recruitment of prisoners.

In late 2024, Ukrainian and American security officials said that around 12,000 North Korean soldiers had been deployed to the Russian army. In January, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky said that 4000 North Koreans had been killed.

In November 2022, Vladimir Putin issued a decree, according to reports in Russia and Ukraine, allowing foreigners to join the Russian army, offering expedited Russian citizenship in return. Now, Josimar can reveal that the Russian army has taken recruitment to new extremes: jobless migrant workers in Qatar as well as unemployed young men in several African countries are being targeted.

“Is my husband okay?”

On 24 April, Marfo Nicholas Kwaku shared a photo on Facebook, posing in front of a car. The picture was taken in the provincial town of Tutayev in the Yaroslavl Oblast region, 300 kilometres northeast of Moscow. This has been confirmed by using geolocation.

Marfo Nicholas Kwaku in Tutayev in April.

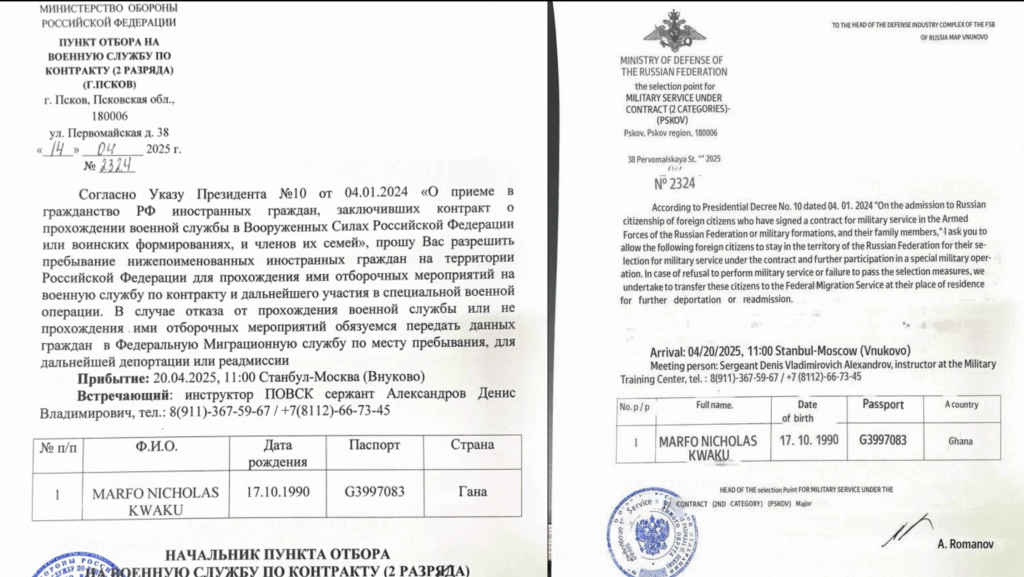

Four days earlier, his flight had landed at Vnukovo International Airport in the Russian capital. Here, according to his Russian visa, he was met by sergeant Denis Vladimirovich Alexandrov, an instructor at a military training centre. A travel agency, run by a husband and wife, took the 35-year-old to his next stop, the Russian army’s recruitment office for military service under contract, category 2, in the Pskov region, which borders Belarus to the south.

“Is everything okay with him? Is my husband okay?” asks Rebeccah Marfo, his wife from a rural area in Ghana, her voice repeatedly trailing off and breaking down. “Perhaps they are training and not allowed to use phones for some time?”

Born on 17 October 1990 in Khumasi, Marfo was the second youngest sibling in a family of three sisters and two brothers – Dora, Vivian, Esther and his younger brother Richard Frimpong, who was born eight years later. His parents are subsistence farmers; they plant maize and cassava during the rainy seasons and cocoa at other times. Marfo’s upbringing was simple, one based around the rural community in Wiamose in the Ashanti region.

“I consider it a happy childhood because my brother and I got the opportunity to get an education,” said Richard Frimpong. “Our parents instilled discipline in us, making sure that our academic performance didn’t fail.”

Richard Frimpong went on to become a nurse after graduating from nursing school. Marfo was a teacher at the Methodist Primary School, teaching physical education and social studies. He earned around 90 dollars a month, not enough to provide for his wife and two children.

“We are both teachers,” says Marfo’s wife.

“We did everything together. Work, go to church, watch movies and he would always tell you that with God everything is possible. I said, ‘you need to fight for a better future’.”

Next stop Doha

In November and December 2022, all eyes were on Qatar and the World Cup, a tournament that ended in a triumph not only for the trophy lifters Argentina, but also for the hosts. When Qatar won the bid for the world’s biggest sporting event after a corrupt vote by the Fifa executive committee in 2010, an already booming construction industry went into maximum overdrive. In just twelve years, the country had to transform its infrastructure; building a new airport, new highways and roads, hotels, a brand-new metro and seven new football stadiums. This required workers, a lot of them. In 2010, Qatar had roughly 1.2 million migrant workers, a number that almost doubled in the years leading up to the World Cup.

In 2019, Marfo Nicholas Kwaku decided to move abroad to seek a higher salary to provide for his family. He was one of the hundreds of thousands hailing from Africa who went to one of the world’s richest countries in search of a job. He dreamed of Europe, but had to settle for Qatar, where unlimited wealth and an uptick in job creation ahead of the 2022 World Cup promised a bright future.

He got a job at Ocean Fish, a seafood producer that promises the best smoked salmon you can get in Qatar. On its website, the company writes: “We are the first smoked salmon producer in Qatar and the largest in the Middle East with a facility of over 4000 square metres. All our smoking is done by our Danish smokemaster according to old Danish family smoking traditions. Our salmon is supplied by smaller family farms from the very north of Norway to secure a superior quality.”

Ocean Fish was founded by Charlotte Trading & Contracting, and is owned by Sheikh Hamad Bin Thamar Al Thani, the chairman of state broadcaster Al Jazeera, according to the Qatar Development Bank.

The kafala system

Like so many migrant workers before him, Marfo, says his brother, found dystopia: long working hours, the monthly minimum wage of 1,000 Qatari riyals (250 euro), wage theft, and dirty accommodation.

“The Arabs weren’t treating the Africans well with racist comments,” says Richard Frimpong. “But he went there for financial reasons, so he didn’t consider such things to hurt him because he was not going to stay in Qatar forever.”

When Marfo arrived in the desert country, there was building activity around the clock. At each of the World Cup stadiums, hundreds of workers would be hard at work on the night shift. About two million migrant workers from some of the world’s poorest countries were brought here to help Qatar deliver the World Cup. For years, the vast majority of the workers were subjected to working conditions that ranged from harsh to hellish. Qatar, like their neighbours United Arab Emirates and SaudiArabia, practised the notorious kafala system, often giving employers’ absolute power. Passport confiscation, excessive working hours and wage theft were – and are still – common. The workers also needed their employers’ approval to change jobs or to leave the country. An even grimmer statistic was the death rate. An Amnesty report from 2021, quoting the government’s own data, said that more than 15,000 non-Qataris had died from 2010 to 2019. Heat stress was the most common cause of death.

In the years leading up to the World Cup, Qatar promised significant labour reforms which, in effect, would abolish the kafala system but implementation did not follow and the vast majority of the migrant workers are still subjected to labour abuse.

Today the endless noise from construction sites has fallen silent in Doha. As a result, a record number of migrant workers are left jobless – and in many cases, stranded. Desperate both for an income and a way out of the country, these workers are easy targets. Many arrived in Qatar burdened by substantial debt, having paid recruiters or manpower-like agencies in their home countries several thousand euros or dollars for the opportunity. Often, families had sold property or land, borrowed from family members or loan sharks for the worker to get the visa to Qatar.

Returning with little or nothing to show for, is not an option. The debt to the recruiter remains, leaving families in even greater despair. But for the recruiters and the manpower-like agencies something has changed this past year. A new market has arisen. Russia.

The airport

It’s 48 degrees Celsius and breathing is difficult even inside our taxi with air conditioning. On this late August day, there are more staff than travellers at Doha International Airport. Only a handful of passengers are waiting at departures. A young man from Nigeria sits in misery after having missed his flight back home, a woman wearing a niqab scrolls through TikTok videos. Outside the main entrance, a man is sleeping on top of his suitcases.

Through this airport, tens of thousands of African migrant workers travel, mostly to and from Africa. Now something has changed. Many African men are boarding the direct flight from Doha to Moscow – to fight for the Russian army in the war against Ukraine. Not all of those recruited in Doha take the direct route to the Russian capital. Recruiters say the most common path is a transit flight through Istanbul.

Employees at Doha International Airport confirm that Africans have become a regular sight on the flight to Moscow.

“Yes, this has been going on for months”, one staff member says. “There are usually not that many and rarely more than ten per flight.”

Recruiting for Russia

Marfo Nicholas Kwaku gradually became worn out by the working conditions in Doha. Qatar was a world of hardship and inequality. “A married man back home, having a room with your children and your wife, and right now you are sharing a room with four people that you don’t know,” says Richard Frimpong.

Josimar has reported and detailed labour abuse in the Gulf nation for years, including after the World Cup. Migrants working on World Cup projects told stories of horrific abuse.

Today, Qatar is one of the avenues where migrant workers might fall foul of a fate that is even more grim than the common consequences of kafala: they are offered a route to Russia and its army, enticed by promises of a high salary, a role far from the front line and Russian citizenship. They are told they will work in logistics or as chefs.

It’s an attractive pitch to workers who are out of work. Official statistics are not available, but eyewitness accounts and anecdotal evidence strongly suggest that the Qatari job market has slowed down considerably in the aftermath of the World Cup.

Marfo had been hatching a plan to depart Qatar when he was approached by a recruiter who tempted him with a wage that for Marfo was a small fortune. He was told that he would work in the background, as a cook preparing meals for fighting soldiers.

In a phone call, trying to lure another African worker in Qatar, the recruiter said that 4,000 Riyals (1,000 euro) would be enough to fix a Russian visa.

Did Marfo truly understand what he was getting himself into? Did he expect to carry a rifle on 15 May? Marfo received a single-entry, tourism visa via a travel company in Saint Petersburg. After a couple of weeks at home in Ghana, he travelled to Russia, via Istanbul, on 20 April, where he was picked up at Moscow’s Vnukovo airport.

Top photo: Marfo’s visa in Russian and English.

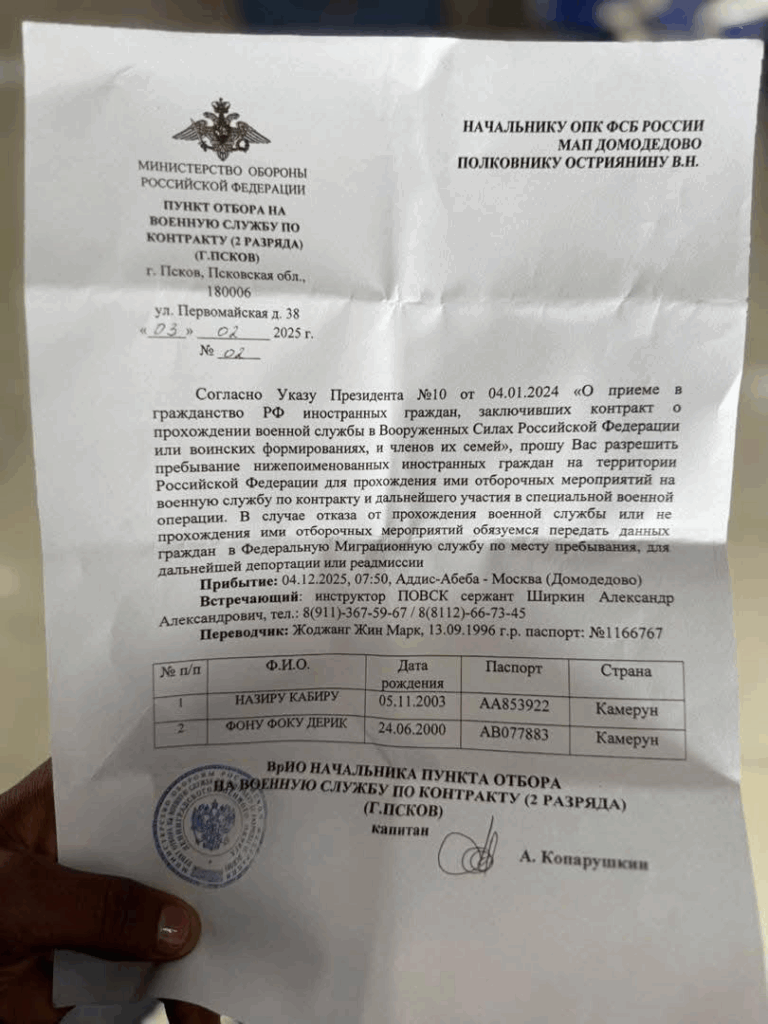

Bottom photo: Visa for two young men from Cameroon.

The instructor’s name is the same for all documents – Denis Vladimirovich Alexandrov.

The Cameroonian recruits

He was not the first West African to end up in the Russian army. Cameroonian media reported on the trap set up by Russia to ensnare their citizens. Yondjou Fabrice was lured to Russia via deceptive travel networks, believing he was going on a tourist visa, but got enlisted through opaque paperwork in Russian and ultimately died in combat.

“The enlistment of Cameroonians in the Russian army is reaching alarming proportions, with dozens of confirmed deaths on the Ukrainian front,” wrote 237online.com in April. The report says that 38 Cameroonians had died, calling “the reality on the ground chilling.”

An investigation “Morts pour la Russie” by leading magazine Jeune Afrique revealed that thousands of Cameroonians and Ivorians have joined Russian forces since the war began. Since the start of the war, hundreds of Central Africans – nicknamed the ‘Black Wagners’ – became Russian soldiers.

In the Jeune Afrique exposé, the migrant soldiers tell horrifying stories of being treated as cannon fodder by the Russian army. A deserter from Central Africa said he was sent on multiple missions to expose Ukrainian positions. According to the deserter, they were told to collect bodies or march several kilometres just to identify targets, often waiting until Ukrainian forces opened fire.

The magazine also documented how Russian forces have woven a recruitment web targeting vulnerable people in poor African countries as well as migrant communities inside Russia. These individuals – Les tirailleurs de Poutine – are enticed or coerced into fighting in Ukraine under Russian command, often with limited understanding or choice.

Russia also targets soldiers on the African continent on active duty in their respective countries’ armies. In a report, the ISS (Institute for Security Studies) highlighted that Cameroonian soldiers have been deserting the country’s army: “What distinguishes this wave of desertions is that soldiers are abandoning their posts to join a high-intensity warzone. Using local networks of recruiters, Russia has attracted numerous Cameroonian soldiers. Some, interviewed by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), reported monthly salaries of 1.2 million Central African francs (1,976 dollars) to 1.5 million Central African francs (2,479 dollars), with specialists receiving at least 2 million Central African francs (3,294 dollars).”

Njoya Mbouombouo is a Cameroonian who didn’t return from Russia. In February, he arrived on a tourist visa but his plans quickly turned into a nightmare. Trained as a plumber after attending a technical high school, Mbouombouo had been out of work when he signed up for employment in Russia, restoring buildings in Crimea.

A recruitment agent who advertised Russian language courses in Moscow told Josimar that he could arrange a Russian visa for 2.5 million Central African francs (3811 euro). He said: “We deal with students and when it comes to the army, we don’t know anything. We couldn’t tell you a thing with certainty about the army.”

“When you arrive in Russia, they hold your passport and make you sign an employment contract that you don’t read,” said a relative of Mbouombouo, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the fear of reprisals. “It’s written in Russian. When you sign this employment contract, a bus comes to pick you up and drops you off somewhere you don’t know. They give you two conditions. Either you cooperate and they’ll give you a week of military training and they’ll send you to Ukraine, or they will kill you – the choice is yours.”

Mbouombouo’s parents and three younger sisters survive on less than six euro a day, according to the same relative. The last time Mbouombouo and the relative spoke, he was near the battlefield and deeply afraid.

The circumstances of Mbouombouo’s death remain unclear. His family never received official confirmation from the Russian consulate in Douala, and his body was never repatriated.

The relative explained: “After his death, the family didn’t really have the opportunity to understand exactly what happened. The official statements denied that he died on the battlefield. But we know he died. He made a video in a bunker with the Russian soldiers, and even in a truck where he was going to supply the soldiers at the front with ammunition and food.”

The shock

Marfo’s enlistment letter, bearing the letterhead of the Russian Ministry of Defence, read: “According to Presidential Decree No. 10 dated 04.01. 2024 “On the admission to Russian citizenship of foreign citizens who have signed a contract for military service in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation or military formations, and their family members,” I ask you to allow the following foreign citizens to stay in the territory of the Russian Federation for their selection for military service under the contract and further participation in a special military operation. In case of refusal to perform military service or failure to pass the selection measures, we undertake to transfer these citizens to the Federal Migration Service at their place of residence for further deportation or readmission.”

Marfo had kept it a secret from his wife that he had enrolled in the Russian army, but told her in a telephone call. “That was a shock,” recalled Rebeccah Marfo. “Can you do it?, I asked. They were at a training camp. I felt scared. I heard that – if you don’t kill, they will rather kill you. I don’t know if he is…there or not.”

Five days after Marfo shared the photo of him posing beside a car in Tutayev, some 300 kilometres north of Moscow, he posted for the last time on Facebook on 29 April. His brother recalls their final contact on 15 May, when Marfo sent him photos in uniform. Four days later, he was in touch with his wife, but then his WhatsApp account went silent. Since then, neither his wife nor his brother has heard from him. In June, they reached out by email to the Russian embassy in Accra, but their message went unanswered.

“Maclean, the first-born, will ask about him,” said Rebeccah. “He always asks about his father. I told him that daddy has gone to work and that he will call later. Now, he has stopped asking.”