The 2010 Fifa World Cup official anthem "Waka Waka" was meant to raise a fortune for African charities, but no money has been forthcoming since 2014. Josimar can tell where some of the missing millions have gone.

By Philippe Auclair

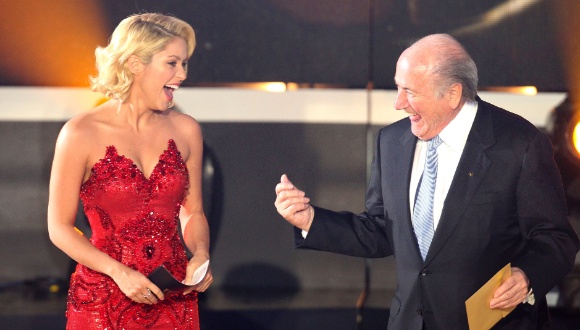

"Waka Waka (This Time For Africa)" is unique among "official World Cup anthems", which are generally forgotten as soon as they've been played at closing ceremonies. It was a huge, bona fide global hit for its main performer, Colombian "Queen of Latin Music" Shakira, who had teamed up with American producer John Hill and South African multi-racial band Freshlyground for the occasion. "Waka Waka" went platinum in the USA, diamond in France, Brazil, Germany and Sweden, and topped the charts in another eleven countries worldwide, including Italy and Spain, where it remained numero uno for over fifteen weeks. Its video has clocked over 4.3 billion views – and counting – on YouTube. With close to one billion streams, it is Shakira's fifth-most popular song on Spotify.

It was all for a good cause. A joint statement published by Fifa and Sony Music on 26 April 2010 announced that "All proceeds (our italics) from the song [would] benefit FIFA’s Official Campaign of the 2010 FIFA World Cup “20 Centers for 2010", which "[aim] to achieve positive social change through football by building twenty Football for Hope centres for public health, education and foot...