Are you a club owner looking for how to bend the rules of multi-club ownership? Just ask Uefa, and they will tell you how to circumvent their own rules.

By Philippe Auclair

"No one may simultaneously be involved, either directly or indirectly, in any capacity whatsoever in the management, administration and/or sporting performance of more than one club participating in a UEFA club competition".

"No individual or legal entity may have control or influence over more than one club participating in a UEFA club competition".

(Regulations of the Uefa Champions League - Article 5: Integrity of the competition/multi club ownership, 2025)

Clear enough? It should be, but it isn't.

On one hand, Crystal Palace have just been demoted to the Uefa Conference League because key shareholder John Textor, who also owns Olympique Lyonnais, failed to divest from the London club before Uefa’s 1 March deadline.

Two other clubs which had qualified for the 2025-26 Conference League, Irish side Drogheda United FC and the Slovakian club DAC 1904 Dunajka Streda, have been kicked out of that competition by Uefa when they were found to be in breach of those MCO regulations (*).

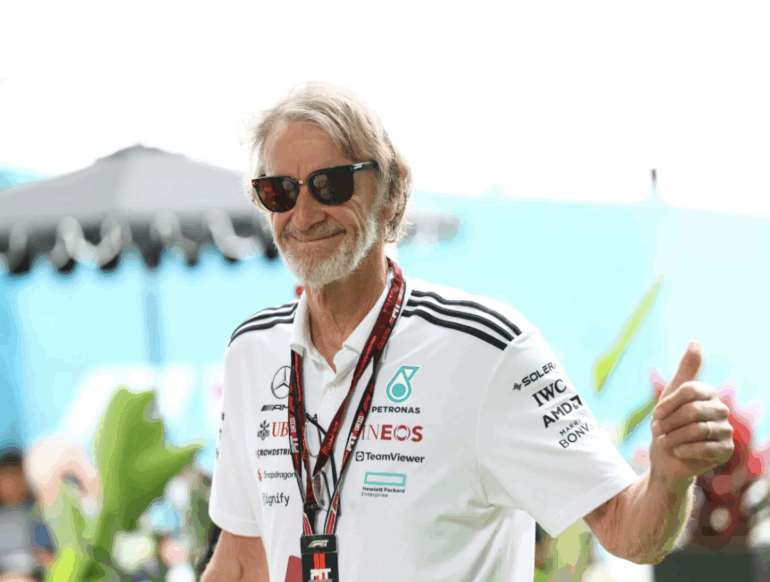

On the other, had Nottingham Forest managed to hang on to a top 5 spot in the Premier League, they'd have been admitted in the Champions League despite being owned by shipping magnate Evangelos Marinakis, who also controls newly-crowned Greek champions Olympiacos. AAnd had Manchester United not endured awful seasons a...